Maybe You Should Talk to Someone: A Message that Resonates

By Asma

I began seeing a therapist regularly when I turned 25 and my sessions mainly focused on my issues with my family. Within a few sessions, I realised that I wasn’t as faultless as I thought. To my dismay, I realised that I had a significant role to play in the issues with my family that I was bringing up in therapy. I hated admitting or even accepting that I was at fault.

My conundrum was that I wanted my therapist to like me. (If I’m perfectly honest, that hasn’t changed. I still want my therapist to like me and I’d like to be their favourite patient.) If you’re wondering, yes, I was in fact the teacher’s pet in school and I really loved it!

Like any self-respecting perfectionist, I set all my attention on achieving my goal – becoming my therapist’s favourite patient. After a good amount of thinking and planning, I came up with the holy trifecta – a well-planned mix of self-awareness, self-deprecation, and fake modesty – to make my therapist like me and to make me seem like I had my life sorted out. I had a more practical motive as well – I assumed that if my therapist liked me, then I wouldn’t have to deal very deeply with my own issues and I’d be let off easily, much like I was in school.

I began peppering my narrations in therapy with healthy doses of self-awareness. Yes, I was engaging in unhelpful patterns repeatedly to no avail, but at least I was emotionally intelligent enough to be aware that I was doing it. Didn’t that warrant some praise and credit? How often did patients come into a therapist’s office and admit that they were repeating unhelpful patterns? Self-deprecation came to my aid when I was talking about an instance where I felt especially vulnerable (often circumstances where I felt quite hurt and didn’t know how to work through my feelings). I’d begin by saying, “Since I’m a genius…” to lighten the mood and reduce the gravity of what I was about to say. Fake modesty was an obvious addition because I thought to myself, “Who doesn’t like a modest person?”

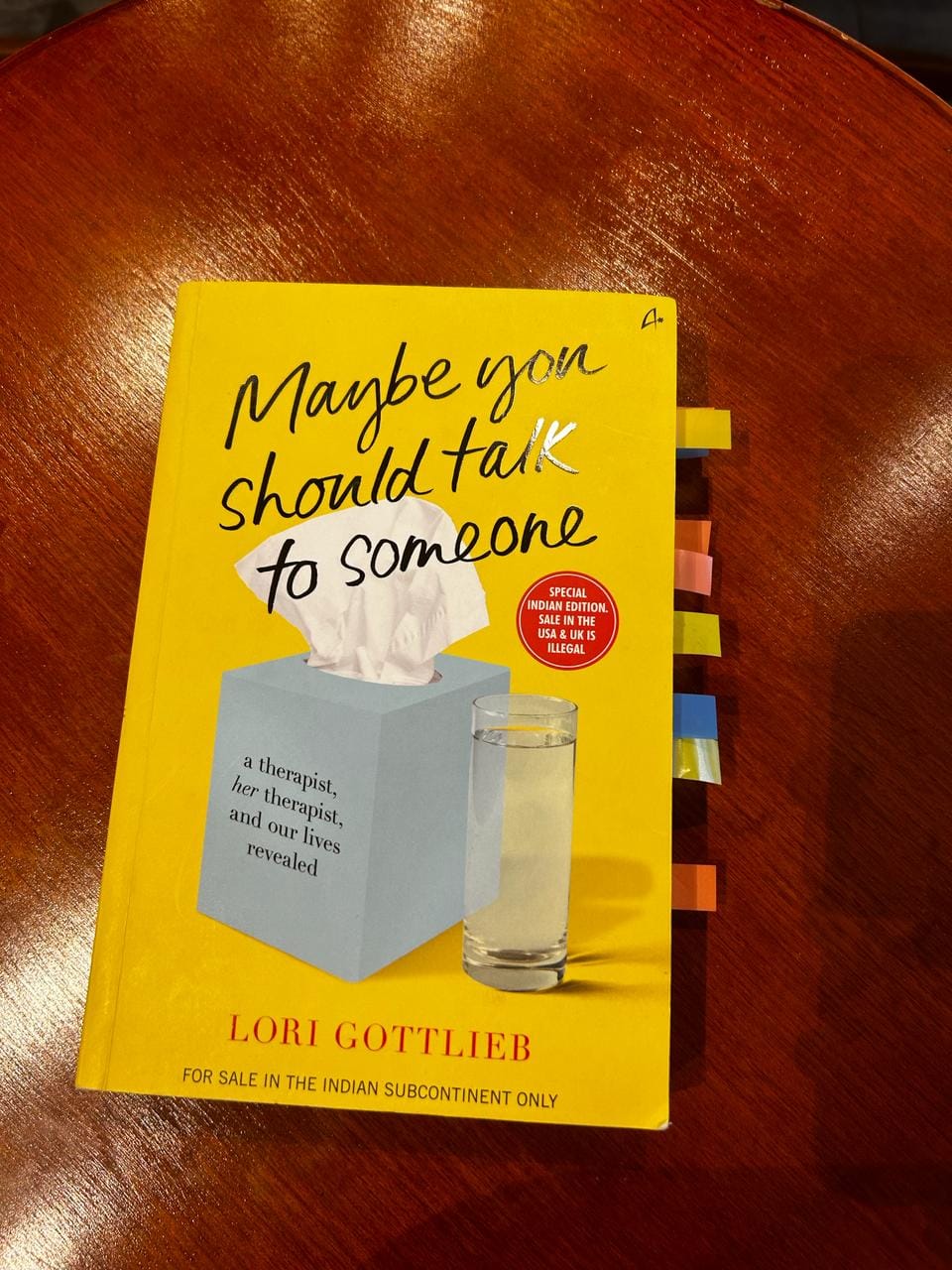

I came across the book ‘Maybe You Should Talk to Someone’ by Lori Gottlieb in 2023 and finished it within two days. In the year that has passed, I have gifted copies of the book to numerous friends.

Lori Gottlieb is a psychotherapist, New York Times bestselling author, a co-host of the ‘Dear Therapists’ podcast, and a columnist for The Atlantic, where she writes the column ‘Dear Therapist’ weekly. ‘Maybe You Should Talk to Someone’ (published in 2019) has sold over a million copies and is being developed into a TV series as well.

Reading Gottlieb’s book disabused me of the notion that I was successfully getting away with my trickery during therapy. I realised that I was spending an inordinate amount of energy in continuing this ruse of perfection and that my therapist probably saw through it. In a way, it was a relief. I could give up the pretense of being the perfect patient.

Over the past year, I have begun working with a new therapist and have limited my tendency to use self-deprecating humour and fake modesty. I still use overt expressions of self-awareness but I believe I will be able to let go of that and become more authentic over time.

Gottlieb’s book chronicles her sessions with her therapist, Wendell Bronson, and her sessions with four of her own patients – John, a successful Hollywood producer with Emmy-award winning television shows to his credit; Julie, a young professor who receives a cancer diagnosis right after her honeymoon; Rita, a woman who plans to end her life in a year if it doesn’t improve, and Charlotte, a young woman who indulges in self-destructive behaviour and makes poor relationship choices.

Gottlieb weaves in details about her own life and experiences throughout the book, creating a fascinating picture of her life. Gottlieb’s path to becoming a therapist is unusual. She starts out as an assistant at a talent agency in Hollywood, works at NBC, decides to become a doctor in her late twenties and joins medical school at Stanford, all before finally training to become a therapist.

Gottlieb begins seeing a therapist while working as a therapist herself, in response to a sudden breakup. Through her skillful storytelling, she introduces numerous concepts about therapy, interspersed them with anecdotes from her life, her sessions with her therapist, and her sessions with her patients.

One such concept is that of the presenting problem. She writes, “By definition, the presenting problem is the issue that sends a person into therapy. It might be a panic attack, a job loss, a death, a birth, a relational difficulty, an inability to make a big life decision, or a bout of depression.”

She writes, “Study after study shows that the most important factor in the success of your treatment is your relationship with the therapist, your experience of “feeling felt.” This matters more than the therapist’s training, the kind of therapy they do, or what type of problem you have.” This is an important fact for people who are considering therapy, who may feel overwhelmed by the various types and modalities of therapy that different therapists offer.

In a way, the book feels like an enjoyable peek into the therapeutic process, where the reader journeys along with Gottlieb and her patients as they navigate through life. Early on, Gottlieb establishes that most people are “unreliable narrators”, not because they intend to deceive their therapists but because they leave out parts of the story that don’t match their perspectives. Reading this was a huge relief for me in my own therapy sessions as it reduced the pressure that I felt to be perfectly objective in what I was saying, lest I be held accountable for presenting only one side of the story.

Despite the nature of the subject of the book, Gottlieb manages to make it incredibly funny, enjoyable, and relatable. When describing the abrupt way in which her boyfriend ends their relationship, she writes, “When my therapist friends hear this part of the story, they immediately diagnose him as “avoidant.” When my non therapist friends hear it, they immediately diagnose him as “an asshole.””

At another point, while describing a patient named John, who is initially rude, uses his phone during a session, and sarcastically calls her “Sherlock”, Gottlieb writes,

“…I felt confident that I could grow to like John. Underneath his off-putting presentation, something likeable – even beautiful – was sure to emerge.

But that was last week.

Today he just seems like an asshole. An asshole with spectacular teeth.

Have compassion, have compassion, have compassion. I repeat my silent mantra then refocus on John.”

Gottlieb’s actions throughout the book and her skill in re-telling anecdotes from her life make her incredibly relatable.

During a session with another patient a day after her breakup, Gottlieb realises with dread that she is wearing a pyjama top emblazoned with ‘NAMAST’AY IN BED’ after the patient asks if she is in fact wearing a pyjama top.

Gottlieb seeks out a therapist following an abrupt break-up initiated by her boyfriend of two years whom she had planned to marry and spend the rest of her life with. In one of her initial sessions with her therapist, she carries pages of notes that are numbered, annotated, and in chronological order, that contain the details of a conversation with her ex-boyfriend. She proceeds to read from the notes where she quotes her ex-boyfriend verbatim.

This was incredibly funny and relatable to me since I have done something similar myself, the only difference being that I carry a journal with pages marked with post-its (much like my copy of Gottlieb’s book in the picture) of conversations with my family. Reading Gottlieb’s account of her actions was hilarious and helped me feel more connected to her.

Maybe You Should Talk to Someone makes for a delightful read. It is simultaneously informative and hilarious because of Gottlieb’s skill at writing. I would recommend it to everyone, irrespective of whether or not they are interested in seeking therapy because of the insight they are likely to derive from Gottlieb’s skillful exploration of her life and emotions and those of her patients.

Views expressed are personal

Asma is a feminist writer with an interest in public policy and mental health. She can be reached on Instagram at @asmag7

You can also read:

Member discussion